The relationship between the Mormon Church and polygamy is a complicated one. The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints (LDS), the original Mormon Church, was founded by its prophet Joseph Smith, Jr. in 1830. Smith took several wives before he officially made polygamy a sacred commandment of Mormonism in 1843. He claimed to have received a direct revelation from God about polygamy and held that it was necessary to fulfill the Biblical charge “to multiply and replenish the earth,” to justify his declaration.

Many of Smith’s followers initially resisted the idea, but Smith told his congregation that the practice was not an invitation, but a divine commandment. He called it “the most holy and important doctrine ever revealed to man on earth.” If a man did not take more than one wife, he would not reach the “fullness of exaltation” in the afterlife; heaven, in other words. Not surprisingly, plural marriages became more and more common among the early Mormons, some practiced secretly and some publicly. The LDS Church announced its advocacy of polygamy in 1852, and when Smith died in 1844, he still believed whole-heartedly in his revelation.

The United States government did not share Smith’s passion for polygamy. Officially, it called plural marriage a “lewd and lascivious cohabitation,” and declared it illegal in 1862. Political pressure from the government mounted and LDS church leaders were threatened with the confiscation of their property and the dismantlement of their church if they did not stop sanctioning plural marriages. By 1890, after days of fasting and praying about the issue, the president and prophet of the LDS Church claimed to have had a direct revelation from God to rescind the practice. He later stated that anyone who continued to live polygamy would be excommunicated from the LDS Church. This begot the first exodus of polygamist Fundamentalist Mormons from the United States to northern Mexico.

My paternal great-grandfather was a polygamous Mormon and in 1902, he brought his wives and children to Mexico as part of this first wave of Mormon migration. At the time, there were six Mormon colonies established in the northern Mexican states and approximately 3,500 fundamentalists were living in the area. My grandfather, Alma Dayer LeBaron, grew-up traveling back and forth between the United States and Mexico until 1924, when he snuck across the US border into Mexico to live there permanently. He moved to Mexico to escape being lynched by an angry mob of American Mormons who were persecuting him for practicing polygamy.

Alma Dayer LeBaron

My grandfather had been living with his first wife, my grandmother Maud, in La Verkin, a small town in Southern Utah. With my grandmother’s blessing, he took a second wife who was eighteen years old and twenty years her husband’s junior. My grandmother and her sister-wife crossed the border in a covered wagon with my father and his seven older siblings. They met my grandfather in the Mexican state of Chihuahua. Many members of my family still reside there to this day.

It was on their trip south that my grandmother became pregnant with her ninth child, my uncle Ervil. He was born on February 22, 1925, in the small Mormon colony of Colonia Juárez where my grandfather had purchased two red brick homes that had been abandoned by earlier Mormon settlers during the Mexican revolution. While my father would become the beloved prophet of our church and remain in his followers’ hearts years after his death, Ervil was the son who made LeBaron infamous outside the barbed wire fences of the colony.

When my grandfather LeBaron and his families first arrived in Colonia Juárez in 1924, the majority of the local families had rejoined the LDS Church and had abandoned the practice of polygamy. According my family’s beliefs, a line of prophets beginning with Joseph Smith had secretly passed down to my grandfather the authority to represent God on earth. Like Smith, my grandfather had visions and revelations that he believed came directly from God.

In one of my grandfather’s most powerful visions, he was walking alone in the Mexican desert near the border. He saw a house and a voice told him to go inside and upstairs. He did so, and when he turned to look out at the U.S., he saw devastating destruction. The vision foretold that the U.S. government would soon collapse, and the suffering would be so great that God’s anointed people would cross the border into Mexico by foot carrying only what they could on their backs.

By 1944, my grandfather began to build Colonia LeBaron, a safe place where God’s chosen people could prosper and practice polygamy. As a teenager, my father, Joel F. LeBaron, worked hard at my grandfather’s side. But only six years after establishing the colony, my grandfather grew ill. He called my dad to his deathbed and placed his weak hands on his eighth son’s head, anointing my father with the religious authority to represent God on earth and to lead His people from the religious bondage and corruption of the U.S. government.

Joel F. LeBaron

Despite this anointment, my father and his younger brother Ervil initially broke from the tradition established by their father, pledging their allegiance instead to the LDS Church. But this allegiance didn’t last long; they had inherited my grandfather’s personal doubts about the differences in Fundamental and LDS Church philosophy. On a mission trip, my father fasted and prayed before realizing he could no longer support LDS Church leaders and their stance against polygamy. He returned to Colonia Juárez in 1944, where he was dishonorably discharged from his mission and excommunicated from the LDS church for disloyalty and advocacy of polygamy. Ervil followed in his older brother’s footsteps and was excommunicated a month later.

My father received further confirmation of his inherited priesthood four years later when he felt impelled to return to Salt Lake City after not having been to the States for seventeen years. While he was there, he hiked up to a canyon above the city and prayed for a sign to show him that he was indeed the new prophet. When he came down from the mountain, he told one of his younger brothers that he had received his answer: he was the One Mighty and Strong, what our congregation called its prophet.

My father told people he had been visited by nineteen prophets, among them Christ, Abraham, Moses, and Joseph Smith who told him that his revelation was true. He claimed to have touched their hands during the visit, so that he knew he had not been deceived. He took this as the sign to found the Church of the Firstborn of the Fulness of Time, and moved its headquarters to Colonia LeBaron the next year.

My father’s brother Ervil was one of his earliest followers and was soon baptized into the new church. My father called himself the “First Grand Head” and Ervil was appointed president—the highest office just below my dad—of the Church of the Firstborn of the Fulness of Time. Together my father and uncle wrote and published the Priesthood Expounded, a list of fifty questions challenging the LDS Church’s philosophy and authority. The brothers began organizing, preaching, and taking mission trips for their new church in Utah, Arizona, and Mexico, and their converts grew in numbers; quite a few people followed the brothers and bought farms or ranches in or near Colonia LeBaron.

In the summer of 1960, my father and uncle made their way to Ogden, Utah and placed their Priesthood Expounded pamphlets onto the windshields of the cars parked in the temple’s parking lot at the local LDS Church. My mother, Kathy Wariner, her three sisters, and her parents—an average middle class American LDS Mormon family—attended that church and my grandfather Wariner took the stapled pages of Priesthood Expounded from underneath his windshield wiper after attending a Sunday morning service.

Grandpa Wariner read the pamphlet and felt intrigued by its content. He requested a meeting with his church leaders to see if they could help him understand what he had found. In response, my grandfather received a letter of excommunication from the LDS Church. While he was saddened by the church’s harsh treatment of what he felt was natural questioning, he took it as a sign from God that the LeBarons were right. My grandfather met with the charismatic brothers and felt inspired to join their church.

From left back row: Grandpa Wariner, Carolyn (Mom’s oldest sister) Kim (Mom’s youngest sister) my mother Kathy, Judy and Grandma Wariner

My parents dated briefly before my mom became my father’s fifth wife. They took their nuptials in Colonia LeBaron in the summer of 1965. I don’t know how my grandparents felt about their teenage daughter marrying the much older prophet of their new church, but they did not openly oppose the marriage. My mother’s parents attended her small wedding, held in secret, due to the fact that polygamy was illegal both in Mexico and in the United States—although the Mexican government had never enforced the laws against my family’s religious practices.

Mom and Dad on their wedding day

My mom believed, without a doubt, that she had married a prophet of God. Among Church of the Firstborn followers, she was referred to as “a warrior” for God’s purpose. Mom became pregnant with my sister Audrey when she was nineteen years old. She became pregnant again and had my brother Matt eighteen months later, and my brother Luke less than a year after that. I arrived on May 20, 1972, the last of the children she would have with my father.

***

While my father’s family grew, Ervil preached by his side. The two worked closely together for over 15 years before their relationship began to disintegrate. My uncle began taking money from the church for personal use without my dad’s permission. Church of the Firstborn followers started to notice that my uncle was driving beautiful cars and wearing expensive clothes, while his thirteen wives and large families lived in poverty. The church itself was in debt and most of its people lived simply, and in many cases, in extreme poverty. Suspicions of whether or not my uncle was an honest man grew, and my father began to question his brother’s integrity.

The brothers also began to deviate on basic philosophy. My uncle was teaching that God’s broken laws should be punishable by death, citing what early Mormon doctrine called a “blood atonement,” which referred to the shedding of blood as a sacrifice for sins. My dad strongly disagreed with his brother’s position and said that he would not condone a man’s death for any reason. As a result of the growing conflicts, my father made the difficult choice to remove Ervil from his office as president of the Church of the Firstborn.

Ervil split from my father’s church, taking a few families with him, and he founded the Church of the Lamb of God. My uncle claimed to have received a revelation that he was in fact God’s true prophet, the true One Mighty and Strong, and that it was his responsibility as God’s representative on earth to rid the world of all false prophets. My father was at the top of Ervil’s list. In meetings with his growing congregation, Ervil made several verbal threats against my father’s life. My dad heard rumors that he might be in danger, but he never believed that his brother would carry out his threats.

At this same time, my father was preaching that he would be the last prophet on earth before the destruction of Babylon. It was embedded in the doctrine of the church that my father would bring in the millennium of peace depicted in the book of Revelations in the Bible, a time that would come after Jesus Christ’s second coming, when Christ would remain on the earth and rule over the world for a thousand years.

But that is not how history would play out. On August 20, 1972, two of Ervil’s followers, men who had initially been avid believers in my father’s divine authority and who had later converted to Ervil’s church, shot my father in the head and neck in an empty abandoned house after luring him to discuss differences in philosophy. Ervil had ordered the execution to be carried out while he watched a movie in an air-conditioned movie theater and waited for the news of the death of his brother.

Mexican authorities arrested Ervil for my father’s murder, but he was later released. The authorities claimed they had no proof that my uncle had actually pulled the trigger—and of course he hadn’t.

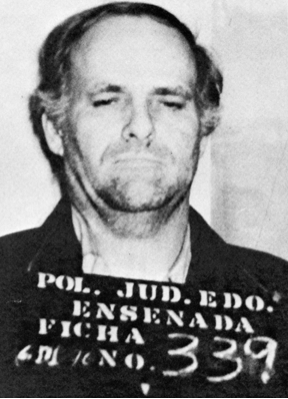

With my father’s assassination, the Church of the Firstborn splintered like a piece of dry wood. Ervil and his followers remained in hiding, running between the US and Mexico as murders of other polygamist leaders in both countries continued to be carried out by the Church of the Lamb of God. It took the authorities eight years to catch up with him, but not before he killed more than twenty-five people, most of whom questioned or doubted his authority. His victims included one of his thirteen wives and two of his own children. Because my uncle never killed his victims himself, but instead ordered his followers to commit these violent acts for him, the media in both the United States and Mexico nicknamed him the Mormon Manson.

Ervil LeBaron after his arrest in Mexico.

Some families left the Church of the Firstborn, with the men claiming my father left them varying levels of authority. Others remained and continued to preach that my father had indeed been God’s true prophet and they waited for a new leader of the church to appear. Although my mother’s parents and sisters left the church shortly after my father’s death, throughout my childhood and even after she remarried another polygamist in Colonia LeBaron, my mom remained a true believer in his teachings and divinity.

The Sound of Gravel is available now

Order from: Amazon | Books A Million | Goodreads | iTunes | Barnes & Noble